Build Your Mental Gym Part 4 of 13: Holistic Regulation Protocols for Freeze State

Introduction to the series:

Build Your Mental Gym: A Brain Health Protocol for Women in Tech (in 13 parts)

You’re ambitious, driven, and focused. You’re constantly climbing, always pushing yourself, and you’ve learned to navigate a world that demands relentless hustle. But lately, things aren’t adding up the way they should. You’re “wired but tired,” struggling with the fog, fatigue, and hormonal chaos. No matter how much you optimise, there’s a nagging sens…

What To Expect:

Stress isn’t always loud. Sometimes, it goes quiet.

You stop reacting. You stop choosing. You stop feeling. You’re not at ease, and you’re just not moving. This is the freeze response: a biological state where your nervous system pulls the handbrake because forward motion doesn’t feel safe or possible.

This state is often misinterpreted as laziness, burnout, procrastination, or indecision. But that misses the point. Freeze isn’t about not caring. It’s about not having access. You may feel numb, unmotivated, shut down, or unable to connect with others. Thoughts loop without resolution. You might overthink small tasks or disconnect from your body altogether. Even rest doesn’t feel restorative because your system isn’t relaxed; it’s stalled.

This response is common when the fight-or-flight pathway has been overused or unavailable, or when you’ve learned to mute your signals to function in high-pressure systems. It can also be more prevalent in nervous systems shaped by chronic stress, trauma, or certain neurodivergent patterns.

The goal here isn’t to “snap out of it.” That’s not how physiology works.

The goal is to create enough safety and sensory input for your body to re-engage. To shift from stuck to steady. From freeze to flow.

Freeze (Disassociation)

Dissociation is the nervous system’s emergency override, a last-resort strategy your body uses to protect you when stress becomes too overwhelming to process. It involves a disconnection from your thoughts, emotions, memories, or even your physical body. One common form is the out-of-body sensation, where you feel like you're observing your life from the outside.

In the short term, dissociation can create distance from immediate distress. But over time, that distance can become disorienting. You may feel numb or spaced out, struggle to identify your emotions, or find it difficult to connect with your sense of self. Your perception of reality may become blurred, and memory can be patchy, either hard to access or slow to form.

This response isn’t random. It's the result of an overwhelmed autonomic nervous system, specifically, a dominance of the dorsal vagal pathway, which drives immobilisation and shutdown. While it might offer short-term relief, it's not a sustainable form of regulation, and left unaddressed, it can make you feel increasingly disconnected from your body, your decisions, and your life.

Physical Signals to Monitor:

🧠 Track Using Interoception (no wearable or test needed)

Immobilization Behavior (due to fear)

What to monitor: Feeling physically stuck, frozen in place, or unable to act in response to stress or fear.

Why it happens: The freeze response activates the parasympathetic nervous system in extreme stress, overriding fight-or-flight with immobility for perceived survival.

Why it matters: Chronic immobility can reduce flexibility, create muscular tension patterns, and increase injury risk.

How to use the signal: If you frequently notice this pattern under pressure, build in gentle, non-overwhelming movement rituals (like rocking, stretching, or walking) to counter it early.

Facial Expressions and Eye Contact

What to monitor: Blank facial expressions, loss of facial animation, reduced or avoided eye contact.

Why it happens: The vagus nerve’s dorsal branch can mute facial expressiveness in the freeze state, which is part of a broader social withdrawal pattern.

Why it matters: These cues impact how others perceive and respond to you, affecting relationship dynamics and co-regulation opportunities.

How to use the signal: If you notice reduced expressiveness or aversion to eye contact, try facial mobility exercises, mirror feedback, or connecting with safe people to re-engage socially.

Depth of Breath

What to monitor: Shallow, irregular, or held breath, especially during moments of stress or decision fatigue.

Why it happens: In a freeze response, breathing slows or becomes shallow as part of the parasympathetic shutdown.

Why it matters: Over time, reduced oxygenation can lead to fatigue, low alertness, and increased reactivity.

How to use the signal: Track when breath becomes shallow and use that moment to pause and initiate a longer exhale or box breathing cycle.

Social Behavior

What to monitor: Withdrawal from conversations, social avoidance, or feeling invisible or "not there" in groups.

Why it happens: The freeze response suppresses social engagement systems in favor of energy conservation.

Why it matters: Isolation can exacerbate nervous system dysregulation, and long-term withdrawal increases vulnerability to anxiety and depression.

How to use the signal: When you catch this pattern, experiment with safe, low-stakes connection (a message to a friend, a short phone call) to gradually reopen the social circuit.

Attunement to Human Voice

What to monitor: Difficulty following conversations, zoning out during human speech, or reduced responsiveness to vocal cues.

Why it happens: Freeze response dampens the middle ear muscle tone, reducing sensitivity to voice frequencies.

Why it matters: Poor attunement impacts learning, social bonding, and workplace communication.

How to use the signal: Use music therapy, vocal toning, or conversation in safe environments to re-engage this neural loop.

Sexual Responses

What to monitor: Decreased libido, difficulty with arousal or intimacy, or feeling disconnected from sexual self.

Why it happens: The body deprioritizes reproduction under extreme stress, diverting resources to survival.

Why it matters: Suppressed sexual function over time can affect relationships and signal chronic nervous system imbalance.

How to use the signal: Track these changes and, if persistent, explore nervous system regulation alongside pelvic floor therapy or trauma-informed support.

⌚ Use a Wearable

Resting Heart Rate

Note: RHR is different from HR. RHR (Resting Heart Rate) is your heart rate when you're completely at restIt’s a stable baseline indicator of overall cardiovascular health and stress load. HR (Heart Rate) refers to your heart rate at any given moment. It fluctuates constantly based on activity, emotions, posture, hydration, and more. Think of RHR as the signal you track over time to assess recovery and chronic stress, while HR is the moment-to-moment metric that can tell you how your body is responding right now.

What to monitor: Lower-than-usual resting heart rate or sudden drops in heart rate during daytime lulls.

Why it happens: The freeze state slows down the heart to conserve energy and reduce detection in threat scenarios.

Why it matters: Persistently low heart rate can reduce oxygen delivery and may signal bradycardia or vagal overdominance.

How to use the signal: Monitor your daily baseline and note any patterns. Use gentle up-regulation practices like humming or movement if rates remain unusually low.

💡 Healthy range: 60–100 bpm resting for most adults. Below 60 may require investigation if symptomatic.

Temperature

What to monitor: Cold hands and feet, or sudden drops in extremity temperature not explained by environment.

Why it happens: Peripheral vasoconstriction redirects blood to core organs in freeze states.

Why it matters: Chronic coldness can impair circulation and thermoregulation.

How to use the signal: Use wearable temperature or skin sensor data. Warm compresses, breathwork, or slow movement can help restore flow.

💡 Healthy range: Extremities should remain warm with minimal variation from core body temperature (~36.5–37°C).

Muscle Tone

What to monitor: Sudden limpness, muscle flaccidity, or extreme relaxation not linked to sleep.

Why it happens: The dorsal vagal freeze response reduces skeletal muscle tone.

Why it matters: Ongoing low tone can contribute to weakness, fatigue, and posture instability.

How to use the signal: Track through muscle engagement during exercise or body scans. Integrate isometric holds and gentle resistance to rebuild tone.

🧪 Get a Test

Blood Pressure

What to monitor: Trends in systolic and diastolic readings showing drops, especially when moving from lying to standing.

Why it happens: Freeze states can drop blood pressure due to parasympathetic dominance and slowed heart output.

Why it matters: Chronic hypotension may lead to fainting, brain fog, and poor circulation.

How to use the signal: If you're seeing consistent low readings, especially with dizziness, explore salt intake, hydration, and nervous system regulation strategies.

💡 Healthy range: Ideal is ~120/80 mmHg. Below 90/60 mmHg is considered low for most adults.

Fuel Availability

What to monitor: Blood glucose variability or patterns of mid-day crashes or fatigue.

Why it happens: The freeze state slows metabolism and reduces glucose uptake to conserve fuel.

Why it matters: Prolonged restriction of energy to the brain and muscles can increase fatigue, brain fog, and poor stress resilience.

How to use the signal: If available, use a CGM to track dips and correlate with freeze-prone times of day or situations.

💡 Healthy range: Fasting glucose 70–99 mg/dL. Post-meal spikes should stay under 140 mg/dL.

Endorphins That Numb and Raise Pain Threshold

What to monitor: Numbness to pain or delayed response to injury, especially when stress levels are high.

Why it happens: Freeze triggers a flood of endogenous opioids to dampen pain and facilitate disconnection.

Why it matters: This can mask injury and illness, delaying recovery.

How to use the signal: Notice if you're ignoring signs of injury or burnout. Use body scans and delayed check-ins to reconnect with sensation.

Conservation of Metabolic Resources

What to monitor: Sluggish digestion, low basal metabolic rate, or unexplained weight gain.

Why it happens: Freeze slows all non-essential systems to conserve energy.

Why it matters: Long-term slowing can decrease immune readiness, physical vitality, and hormone health.

How to use the signal: Consider testing for resting metabolic rate, thyroid function, and cortisol rhythm.

Immune Response

What to monitor: Frequent infections, slow wound healing, or chronic inflammation.

Why it happens: Chronic freeze suppresses immune response via vagal inhibition of inflammatory reflexes.

Why it matters: Suppressed immunity leaves you vulnerable to illness and poor recovery.

How to use the signal: If you're frequently sick or healing poorly, it’s a sign to intervene systemically, not just symptomatically.

Behavioural Responses to Observe:

Why I’m Not Offering Behavioural Advice Here (Yet): I’m intentionally leaving this section open for now.

Yes, you can google “how to respond to stress” and find plenty of suggestions — but here’s the thing: most of those behavioural recommendations haven’t been studied on female bodies. They also rarely account for how social conditioning shapes our responses, especially for women. And they almost never consider neurodivergent patterns or how behaviours might look different for people outside the so-called “norm.”

Right now, I’d rather be honest about that gap than offer generic advice. I’ll update this section when (and if) I come across research that feels more rigorous, inclusive, and representative of real-world experiences.

💡 Our focus with this course is to support our body physically through protocols across sleep, fuelling, movement, and environment. Working with a licensed medical expert such as a psychologist, psychiatrist, etc. is one of the protocol recommendations.

The Protocol

Follow these steps, one at a time. Each is designed to gently guide your system out of freeze and back into safety, presence, and momentum.

Step 1: Activate Your Vagal Nerve Through Breath

When your body is in a freeze state, your breathing likely becomes shallow and tight, which is often paired with a clenched jaw and tense shoulders. These are signals of threat. And your body listens. It interprets that constriction as a cue to shut down further.

The antidote for this is intentional breathing. Breathing in certain patterns stimulates your vagus nerve—the main highway of the parasympathetic nervous system—which tells your body it’s safe to soften. It helps shift you out of threat response and into calm. Below are three options. Choose the one that feels most natural today.

Box Breathing: Box breathing is a structured breath pattern that you can use to feel more present in the moment. It can lower your heart rate (RHR), improve heart rate variability (HRV), and shift your nervous system into parasympathetic dominance.

How to do it:

Inhale through your nose for 4 seconds

Hold for 4 seconds

Exhale through your mouth for 4 seconds

Hold for 4 seconds

Repeat for 1–3 minutes

💡 You can also try a 4-7-8 pattern if you want a deeper downshift.

Alternate Nostril Breathing: Also known as Nadi Shodhana in yogic tradition, this breath helps reset your autonomic rhythm. It balances the left and right hemispheres of the brain, enhances HRV, and soothes overactive sympathetic activity.

How to do it:

Place your right thumb on your right nostril.

Close the right nostril and exhale slowly through the left.

Inhale through the left nostril.

Close the left nostril with your ring finger, release the right nostril.

Exhale through the right nostril.

Inhale through the right, then switch again.

Repeat for 10 cycles or until you feel more settled.

Physiological Sigh: This is the fastest way to shift your nervous system out of threat.

How to do it:

Take a deep inhale through your nose

Take a second shorter inhale right after, without exhaling in between

Exhale slowly and completely through your mouth

Repeat 1–3 times as needed

This pattern helps clear CO₂, reinflate collapsed alveoli in the lungs, and reduce physical anxiety symptoms, quickly.

Step 2: Reorient to Your Physical Environment

Now that your body has softened, shift your attention outward. Grounding into your external environment helps deactivate internal alarms. This step is called orienting.

When you’re in a freeze state, your nervous system becomes hyper-focused on threat. That’s defensive orienting. We want to shift that to exploratory orienting, where you look for cues of safety instead of danger.

Start here:

Notice three things you can see that feel familiar or comforting.

Tune into a sound that feels neutral or soothing.

Is there a scent around you that feels safe? Like home, or nature, or something warm?

Your eyes are key messengers. In threat, they dart or narrow focus. To help your brain register safety, widen your visual field.

Try this eye movement exercise:

Extend your arms in front of you and focus on your two pointer fingers.

Keep your head still and focus your gaze on the left fingertip.

Slowly move it diagonally up-left and follow it with your eyes only. Return to center.

Repeat out to the left, and then down-left.

Switch to your right hand and repeat the diagonal up, out, and down motions.

💡 The wider your range of eye motion, the safer your body tends to feel.

Lastly, notice the base of your skull. Your suboccipital muscles often hold tension in freeze. Gently massage or stretch this area to help release residual physical bracing.

Step 3: Relax Your Muscles with Tension and Release

Muscular bracing is a common response in freeze. You might not even realise you’re holding it. This simple tension-and-release practice brings those patterns to awareness and gives them somewhere to go.

How to do it:

Choose a muscle group and inhale as you tense it for 4–10 seconds.

As you exhale, let the tension go completely.

Pause for 10–20 seconds, then move to the next group.

Follow this sequence:

Face and jaw: Squeeze your eyes shut, frown deeply, clench your teeth.

Neck and shoulders: Shrug up toward your ears; tuck your chin to chest.

Arms and hands: Make tight fists and curl your wrists inward.

Chest and stomach: Curl your upper body inward slightly, like a gentle fetal curl.

Hips and thighs: Clench your glutes and quads tightly.

Lower legs and feet: Flex your calves and curl your toes.

Even five minutes of this can discharge stored tension and invite calm.

Step 4: Ground Yourself to Stabilize

Once the freeze begins to thaw, grounding your body in the present helps solidify the shift.

If weather allows, stand barefoot on soil or grass. This simple act of grounding—also known as earthing—has been shown to improve HRV, lower RHR, and regulate circadian rhythms.

If outdoor grounding isn’t available, try the 5-4-3-2-1 technique:

5 things you can see

4 things you can touch

3 things you can hear

2 things you can smell

1 thing you can taste

Do it slowly. Breathe deeply. Repeat as needed. You’re teaching your brain: I’m here. I’m safe. I’m present.

Step 5: Activate Your Physical Senses

Your sensory system is a direct line to your nervous system. When you choose soothing sensory input, you help regulate from the bottom up.

Try this sensory menu:

Sight: Look at a photo of someone you love. Or a quiet landscape.

Smell: Inhale lavender, rosemary, or another calming scent.

Touch: Wrap yourself in something soft. Try a warm bath or massage.

Taste: Sip herbal tea. Let a piece of dark chocolate melt on your tongue.

Sound: Listen to nature sounds or calming music.

Movement: Do something rhythmic like knitting, walking, dancing, or biking.

Use this like a toolkit. Add to it. Customise it. Let your senses become allies.

Step 6: Reach Out

Safety is often relational. If you’re ready, text a friend. Call someone you trust. Or check in with a mental health professional. Just a simple connection can start to rebuild your sense of belonging.

Step 7: Keep Practicing

Once your body starts to feel safer, revisit this protocol regularly—not just during freeze. Think of it as maintenance, not emergency repair. These are tools for long-term regulation.

Use them. Refine them. Make them yours.

Step 8 (optional): Menstrual-Phase-Specific Support

Take note of the below menstrual-phase-specific recommendations to support your physical body in the meantime. You can identify your phase in the period tracking app you are using.

→ Menstruation Phase

Prioritize additional sleep: You might experience more physical exhaustion and need extra rest during this phase. Give yourself that.

Light exercise: Engage in gentler-than-usual activities. Mindful movement is key.

Heat therapy: Apply a warm compress or take a warm bath to relax muscles and ease cramping.

Watch your blood sugar: If mood swings or cravings are common, consider CGM analysis to spot patterns. Spikes may lead to a hormonal imbalance.

Fuel mindfully: Opt for balanced meals with whole grains, fruits, veggies, lean proteins, and good fats. Focus on warming foods like soups and iron-rich options.

Skip restrictive fasting: Avoid stringent fasts that increase inflammation. Speak to a licensed medical expert if needed.

Consider supplementation: Vitamin C, omega-3s, iron, magnesium, and zinc can ease pain and support recovery. Consult a practitioner for dosage.

→ Follicular Phase

If low energy persists: Period fatigue may linger due to rising but low estrogen. Prioritise sleep hygiene and use situational rest strategies.

→ Ovulation Phase

If experiencing ovarian pain or acne: This may indicate issues breaking down estrogen. Cruciferous vegetables and fibre help flush excess hormones.

Zinc support: Zinc is crucial for ovulation, yet natural levels are at their lowest. Add zinc-rich foods like pumpkin seeds and nuts, and consult a practitioner if considering supplements.

→ Luteal Phase

If experiencing cravings: Metabolism is higher; more calories help stabilise blood sugar and reduce PMS. Prioritise fats, proteins, and hydration.

If experiencing pain: Magnesium-rich foods like leafy greens and nuts may ease stress and cramping.

If bloated or foggy: Hydrate well and avoid caffeine and sugary drinks, which dehydrate and elevate heart rate.

Supplement with omega-3s: Found in seafood, flax seeds, and walnuts, omega-3s can ease both physical and mental PMS symptoms.

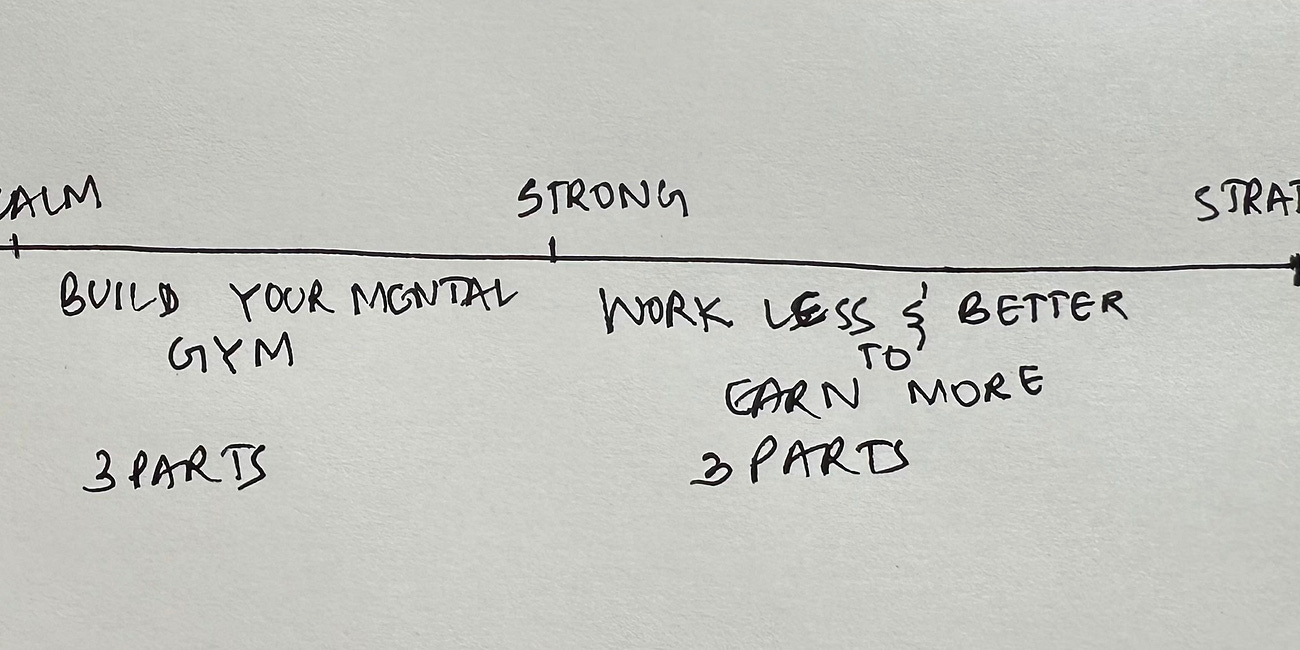

Section 1: Nervous System Regulation

Part 1 of 13: Wired But Tired? Start With Your Nervous System

Part 2 of 13: What Kind of Dysregulation Are You Experiencing?

Part 3 of 13: Holistic Regulation Protocol for Fight-or-Flight (For When Your System is Stuck in Overdrive)

Part 4 of 13: Holistic Regulation Protocol for Freeze (When You Feel Numb, Stuck, or Shut Down)

Part 5 of 13: Holistic Regulation Protocol for Overall Menstrual & Brain Health (Part 1; Part 2)

Part 6 of 13: Understanding Your Type of Tired

Part 7 of 13: Restorative Protocols for the 7 Types of Unrest

Section 2: Build Your Mental Gym

Part 8 of 13: Neurotransmitters: The Gut-Brain Axis and Fuelling for Nervous System Regulation

Part 9 of 13: Neuroplasticity: The Vagus Nerve

Part 10 of 13: Neurogenesis: Interoception and Exposure to Hormetic Stress

Section 3: Work Less & Better to Earn More

Part 11 of 13: Peak Performance Training

Part 12 of 13: The Power of Creative Flow

Part 13 of 13: Productivity 101

Disclaimer: Understanding Research in Female Health and the Female Brain

The content provided in this series, "Build Your Mental Gym: A Brain Health Protocol for Women in Tech (in 13 parts)," is intended for educational purposes only and should not be construed as medical advice, diagnosis, or treatment. The information presented here is based on existing and available research in female health and the female brain, but it is essential to recognize that scientific understanding in these fields is continuously evolving.

1. Limited Scope of Information: The material covered in this series offers a general overview of topics related to nervous system regulation, with a focus on how it pertains to women in the field of technology. While efforts have been made to ensure the accuracy and relevance of the information presented, it is not exhaustive and may not encompass all aspects of female health or brain function.

2. Individual Variability: It is essential to recognize that individual experiences and health conditions may vary significantly. Factors such as genetics, lifestyle, medical history, and environmental influences can all impact an individual's nervous system regulation and overall well-being. Therefore, the information provided should not be applied universally without consideration of individual circumstances.

3. Consultation with Healthcare Professionals: Participants are encouraged to consult with qualified healthcare professionals or medical experts regarding any specific health concerns or questions they may have. While the content presented in this series may offer valuable insights, it is not a substitute for professional medical advice or personalised healthcare recommendations.

4. Evidence-Based Practices: Where applicable, the series content may reference evidence-based practices or findings from scientific research studies. However, it is important to recognise that research findings may be subject to interpretation, replication, or revision over time. Participants are encouraged to critically evaluate the evidence presented and consider the credibility and relevance of research sources.

5. Gendered Nature of Research: It is crucial to acknowledge the historical and ongoing gender biases present in scientific research, which have often resulted in a lack of comprehensive understanding of female-specific health issues and brain function. The underrepresentation of women in clinical trials and research studies has contributed to gaps in knowledge regarding the unique physiological and neurological characteristics of women. As such, participants should be aware that certain aspects of female health and brain function may not be fully understood or adequately researched.

6. Legal and Ethical Considerations: The creator of this series has made reasonable efforts to ensure that all content complies with applicable legal and ethical standards. However, the information provided should not be construed as medical advice.